Nepal: high-risk waste

2024-12-26

© Christophe Da Silva

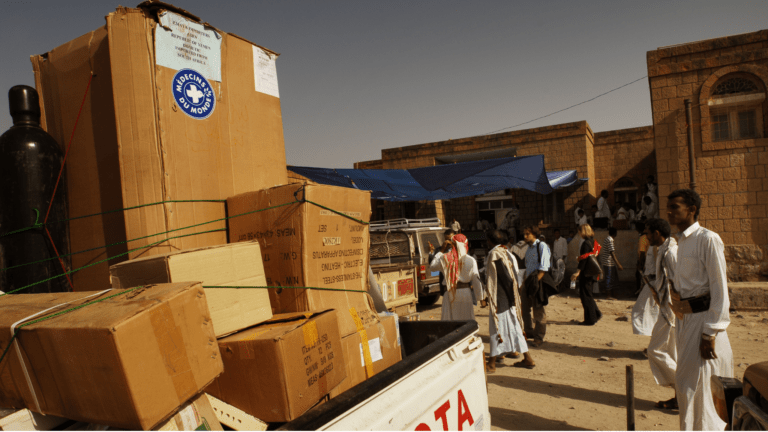

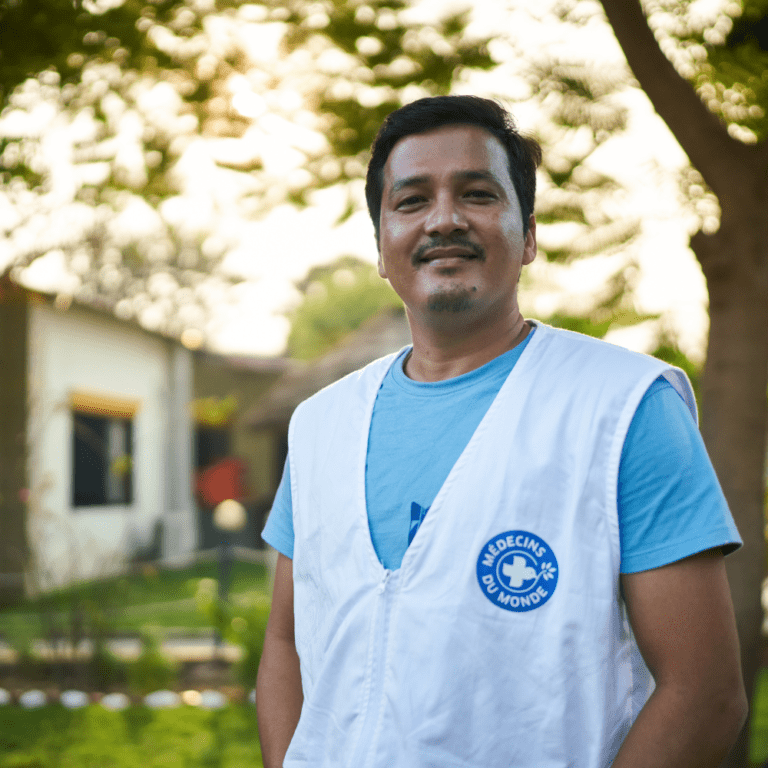

Médecins du Monde has been working in Nepal for 30 years, mainly providing an emergency response to assist a population frequently affected by severe earthquakes. Today the organisation works with the Nepalese community employed in collecting waste, an occupation that directly threatens their health.

The noise is deafening; the smell is unbearable. In the early morning, the sun is already beating down on the Kathmandu valley, silhouetting hundreds of figures thronging the mountains of rubbish at the dump. In the midst of the intimidating ballet of bulldozers and trucks unloading the capital’s rubbish, the waste workers, absorbed in their task, run every risk imaginable to sift through the waste as quickly as possible, collecting a few potentially sellable items to provide an income. “Everyone here is afraid of having an accident, but there are also many other dangers, such as exposure to toxic waste or sharp objects”, explains Jano Dangol, representative of SASAJA (Samyukta Safai Jagaran), the waste workers’ organisation.

‘Low caste’

The waste-processing system in Nepal is complex, and dealing with waste is considered demeaning by the population. As a result, it relies on the efforts of the most precarious in society, whether immigrants of Indian descent or members of so-called ‘low castes’, known as Dalits or Untouchables. Society ignores, stigmatises and is even violent towards these people on the lowest rung of the social ladder. “People do not want them spoken to, or touched,” explains Madan Pandit, who is a door-to-door waste worker. A small minority is employed by the municipal authorities and therefore has certain rights, a salary and equipment. “The rest are informal workers living precariously with no social security or income,” deplores Abdul Saboor Khan, Médecins du Monde General Coordinator in Nepal.

While the threats posed are numerous – cuts, infections, burns, poisoning, exposure to tetanus and transmissible diseases, and musculoskeletal injuries – the options for accessing treatment are extremely limited. “Nepal possesses a fairly effective system of health insurance to cover the population’s basic healthcare needs,” explains Abdul Saboor, “but this is financially out of reach of most of these informal waste collectors.” This major obstacle is made more insurmountable by the absence of support that is tailored to the issues they face and even by a degree of reluctance on the part of health workers to provide them with care.

© Christophe Da Silva

A new health model

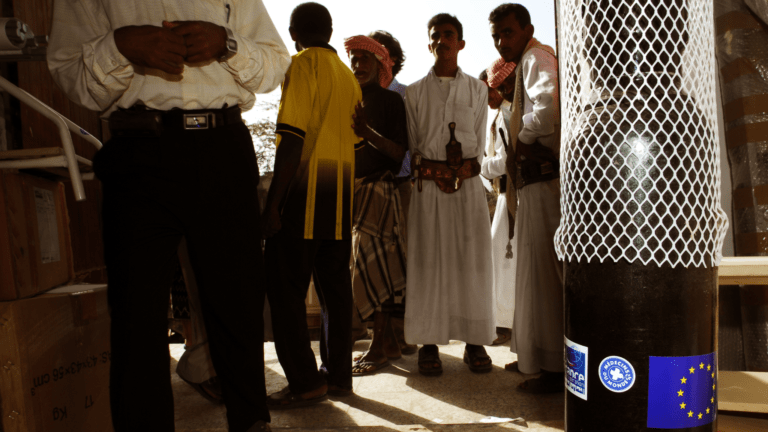

In 2015, when the Nepalese State introduced the concept of the Urban Health Promotion Centre (UHPC) – a new model for community-based health centres catering for the most vulnerable in society and freeing up the country’s seven hospitals – Médecins du Monde saw in this move a real opportunity for inclusive healthcare. But a lack of will or resources led to years passing and nothing being done. In 2019, the organisation decided to set up the first UHPC in Kathmandu. “The idea was to demonstrate the effectiveness and relevance of this type of facility and to hand over the methodology to the State for it to be rolled out across the country”, recalls Abdul Saboor. “But we imposed one condition, namely that a range of care adapted to the specific needs of waste collectors be included in the centres’ provision.”

Today, while the Kathmandu centre meets the needs of some 15,000 inhabitants in the neighbourhood, above all it has become an essential service for informal waste collectors who consult and are treated for free. Aastha Lamichhane, a UHPC nurse, is delighted at this person-centred approach: “They are aware of the immediate dangers posed by their work but much less aware of the more indirect consequences. They are so preoccupied with survival that we see considerable delays in them seeking treatment, which worsens their health issues. So we try to monitor their health proactively, for example by providing free, systematic vaccinations for adults against diphtheria and tetanus.” An ongoing link is maintained through organisations of local waste collectors, such as SASAJA, which works alongside Médecins du Monde to organise awareness-raising activities on the ground.

© Christophe Da Silva

The trial has now proved an outright success: the city of Kathmandu has taken over managing the UHPC and, convinced of its relevance, is currently working to replicate it in 32 neighbourhoods in the capital. “We are continuing to provide backing for the rollout of these UPHCs, directly supporting five of them, and, furthermore, are supporting other paramedical health centres in Kathmandu and Nepalgunj as part of the same vision of ensuring waste collectors and all marginalised sectors of the public are brought closer to healthcare,” explains Abdul Saboor Khan.

The waste pickers are so preoccupied by surviving that we notice a lot of delays in care, which in turns worsens their issues.

UHPC nurse in Katmandou

Fighting for rights

In Nepalgunj, a city on the border with India where Médecins du Monde supported the opening of another UHPC, for more than 500 years the management of urban waste has fallen to the caste known as the Balmiki or Valmiki. “To begin with, we weren’t allowed to occupy any other job. Today we still can’t eat or go to the temple with people from other castes,” explains one of its members, Jagdish Balmiki. Faced with this deep-rooted stigmatisation, Médecins du Monde set about supporting the capacity of these communities to organise and stake a long-term claim on their rights. Jagdish Balmiki is pleased to note that: “Since we have spoken with one voice, we feel more respected, and this helps greatly with negotiating better working conditions.” In Kathmandu, the organisation Sofai Yoddha was created to support the cause of Nepalese recyclers all the way to international summits.

For Abdul Saboor Khan, working hand in hand with the people concerned brings hope. “The Nepalese healthcare system is in the process of evolving in a sustainable way. Challenges remain but we will rise to them.”

Lou Maraval

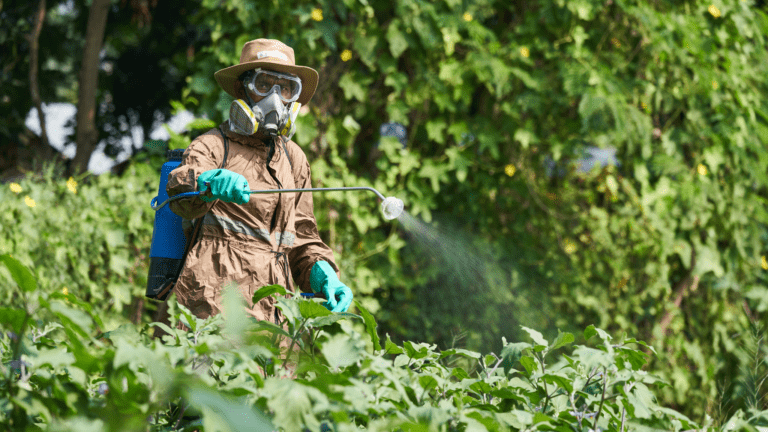

Tarka Bahadur Thapa

Head of the programme in Nepalgunj

“In Nepalgunj, where pesticides are widely used, vegetable growers are also threatened by their work. For example, they risk respiratory and skin problems, tetanus and diphtheria and musculoskeletal problems. We were struck by their glaring lack of access to healthcare given their income is insufficient to cover the cost of health insurance.

Consequently, along with our local partner Bee Group, we developed a flexible healthcare response. First, we have distributed protective equipment and raised awareness of harm reduction practices relating to the use of these products. Second, we have supported the transition of these vegetable growers to organic methods. Lastly, we have helped three health centres to offer appropriate, free treatment, notably covering vaccination and health insurance registration. A large proportion of the vegetable growers receiving support have now turned to organic farming. By working for their health, we are helping protect the health of all Nepalgunj residents.”

© Christophe Da Silva

Médecins du Monde’s activities in Nepal are supported by the AFD (French Development Agency).